🇯🇵日本語

💎 「店の外」に広がった仕事は、全部“お客様の会話”から始まった

岡田さんの現在の仕事は、一言で説明しづらい。

海藻の会社、魚屋、マグロ漁船を持つ生産者サイドの会社、そして作家活動。関わる先は複数に及ぶ。

ただ、始まりは驚くほどシンプルだった。

カウンターですしを食べながら、社長たちが聞く。「なんでその魚が手に入るの?」「どうやって仕込んでるの?」

岡田さんは“教えてしまうタイプ”だと言う。だから全部答える。すると次もまた質問が来る。次回もまた。やがて——その会話が「うちの会社に入ってくれませんか」という誘いに変わっていった。

「うちの会社の中に入ってもらって、その知識とかネットワークとか経験を会社の中に生かしてもらえないかという誘い方をされるんですよね。」

すしを握らない仕事は、狙って作った“転職”ではなく、必要とされた“延長線”として立ち上がったものだった。

💎 魚屋とマグロ漁船の現場で求められたのは「ルート」と「売り方」の設計

魚屋や生産者に対して、岡田さんが提供しているのは “すし職人の技”そのものではない。

むしろ、すし職人として積み上げた「特殊なルートを集める力」や、「これから先の売れ方を考える視点」だ。

魚屋は、昔ながらの売り方でも今は売れている。

けれど魚離れが騒がれ、未来は同じ形で続くとは限らない。マグロも同じ。今は人気でも、会社の平均年齢が高く、SNSやネット販売は得意ではない。だからこそ“何か”が必要になる。

その“何か”を、岡田さんは「SNSを使えばいい」という単純な話にしない。

売り方はツールではなく、これからの打ち手の組み立て。海の現実と、食の未来と、会社の体力を見ながら設計する領域だ。

「今は売れているんだけど、今後のことを考えてちょっと…というような感じで。」

すし職人が現場で求められるのは、包丁だけじゃない。

“海から食卓まで”を一つの流れとして見られる人材が、いま足りていない——そんな空気が、言葉の端々から滲んでいた。

💎 海藻の可能性に火がついた瞬間。「1500種類、全部食べられる」

海藻の会社「シーベジタブル」との出会いも、友人の訪問がきっかけだった。

食の世界に入ってきた友人を祝うように海藻を食べさせてもらい、その美味しさに即反応する。「これは店ですぐ使うよ」。

そこから会話が深まる。

海藻の食文化は、ある地点で止まってしまっている。昆布は出汁、ひじきは甘辛い——それ以外が広がらない。

一方で、日本には1500種類の海藻があり、それが全部食べられて毒がないと聞く。岡田さんは、そこで一気に視界が開けた。

“これから多様な海藻が出てくるなら、食べ方の提案が必要だ”。

トサカノリのように、見つけても「買いたい人がいない」「買っても食べ方がわからない」世界を変えるには、メニュー開発が要る。

その役割を自分が担おう、と提案してジョインした。

「日本には1500種類海藻あるんですけど、それが全部食べられるんですね。」

すしという一点から始まって、海藻という広大な世界へ。

岡田さんの関心はいつも、“海の食べ物”の可能性が眠っている場所に吸い寄せられていく。

💎 原点は18歳。「家にごはんがない」日々が、料理の道を決めた

すし職人としての原点を辿ると、そこには強烈に個人的な出来事がある。

18歳のとき、お母様が43歳で急逝。下には年の離れた妹と弟がいて、家の食生活が崩れた。

コンビニ弁当と惣菜。好きなものだけを選ぶ日々。

その結果、体調に変化が出る。弟が夜になると嘔吐するようになった。

父親も岡田さんも料理ができない。誰がご飯を作るのか。そこで岡田さんは腹をくくる。

大学進学を諦め、「家族に食べさせられる料理を作れる人間になろう」と料理の世界に入った。

華やかなイタリアンやフレンチもある中で、日常の食として和食を選び、そこからすしへ進む。

「家族に食べさせられるような料理を作れる人間になろう。」

すしの道は、憧れや格好良さだけで始まったものではない。

生きるための“食”を立て直す使命感が、最初から芯にあった。

💎 「現場に答えがある」──こだわりは、産地の曖昧さへの違和感から生まれた

修業の世界は、知識だけでは上がれない。技術の積み重ねが絶対に必要で、岡田さんは休みの日も練習し、先輩に挑戦状を叩きつけるように腕を磨いた。

そして独立後、市場に行った時の違和感が、こだわりを決定づける。

アジを買おうとすると、箱には神奈川産、鹿児島産、高知産…でも店員は「これ千葉だよ」と適当に言う、そんな人もいた。

“どこで誰が獲った魚なのか”が曖昧なまま流通している。そのまま握って、お客さんに「何産のアジです」と言えない。岡田さんはそこにしっくりこなかった。

だから、現場へ行く。

ネギはどう作られているのか。大根は誰がどこで育てたのか。食材ごとに生産者を訪ね歩く旅が始まる。

その徹底が、店の食材選びや世界観に直結していく。

「食材は全部現場、答えは現場にあるんだなって思って。」

“こだわり”は趣味ではなく、信頼の設計だ。

岡田さんの仕事の全部が、ここに根を張っている。

💎 紹介制が育てた「人の記録」──お金をかけずに人を喜ばせる技術

岡田さんの店は、紹介制というスタイルを選んだ。

それは聞こえは良いが、実は難しい。紹介された人を、紹介者の顔を立てながらもてなすには、情報が必要になる。

名前と顔を覚えるのは当然。食べたもの、好き嫌い、気づき——それをメモしていく。

ここで岡田さんが言う「個人情報」は、支配や詮索のためのものではない。相手をコントロールするためのデータではなく、相手を“安心させるための手がかり”だ。

誰の紹介で来たのか、どんな背景を持つ人なのか、何を心地よいと感じるのか。そこを外さないために、丁寧に覚える。つまりこれは、プライバシーの侵害ではなく、敬意の解像度を上げる行為に近い。

さらに住んでいる場所などの情報と組み合わせることで、頭の中に“フォルダー”ができる。例えば横浜フォルダー、さらに区ごとのフォルダー。そこに人が紐づく。

それが、会話の精度を上げ、相手を喜ばせ、商売にもプライベートにも効いてくる。

「お金かからずして人を喜ばせるために、そういった個人情報の管理…っていうのを今でもずっとしてますね。」

しかも、その学びの源泉は「お客様」だった。

カウンターには経営者や各分野のプロが集まる。会話の中で、知らないうちにコツを教えてもらっていた。

“人が人を育てる場”としてのすし屋。その濃度が、岡田さんのスタイルを作ってきた。

💎 「普通」だったから、生徒会長になった。敵を作らない“中立”の才能

5段階評価で、岡田さんは自分を「オール3」だったと言う。

突出してできるわけでもない。できないわけでもない。コミュニケーションも普通。コンプレックスもあった。

けれど中学時代、担任の先生が岡田さんを生徒会長に指名した理由は「普通だから」だった。

不良とも話せる。いじめられる子や障害のある子とも話せる。どちらにも行ける中立性が必要だった。

そして岡田さんは、大人になって「八方美人」を肯定する。

敵を作らない。みんなと仲良くする。味方にできなくても、敵を作らない。

それは処世術というより、人間関係を壊さず場を前に進める“技術”に近い。

「僕は八方美人最強説ってのを思ってて。」

この価値観が、複数の会社に跨って信頼される今の働き方とも、まっすぐ繋がっている。

💎 これからは「外に広げる」より、「内側に丁寧に伝え直す」

独立当初、岡田さんはすしの素晴らしさを世界に伝えたいと思っていた。

そのために、すしのカウンターの“緊張感”を和らげたいとも考えた。お金を払う側が緊張しているのはおかしい。もっと楽しく、フラットに食べたらすしはさらに美味しく感じる——そう信じてきた。

でも今、視点は変わっている。

世界にはすしがかなり広がった。自分が“広げる”と言わなくても、すしは広がっていく。

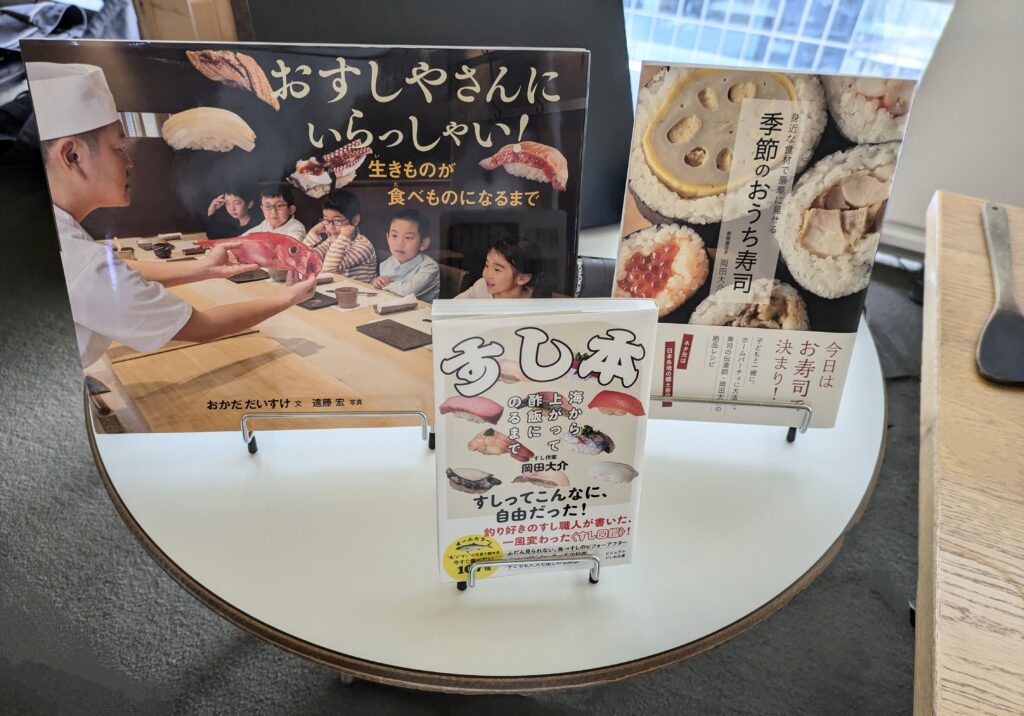

むしろ最近気づいたのは「日本人に、すしが伝わっていなかった」こと。だから、これからは内側へ。子どもにも大人にも、本当の意味のすしの魅力を伝え直す時期だ、と。

そしてそれはすしだけでは完結しない。

海藻がなければ卵を産めない生きものがたくさんいる。海の環境のことも含めて、トータルに海を見ながらすしを伝える——その方向へ、深めていく。

「内側にもう少し丁寧にやり直していくのが必要な時期が来てるなと思っています。」

広げるより、深める。

すしを“食”としてだけでなく、“海”として伝える。

岡田さんの次のフェーズが、ここで定まった。

💎 中学生に1日だけ時間があるなら。「釣りから始める」

最後に語られた教育観が、岡田さんの本質を一番端的に表していた。

中学生に何か体験させられるなら、すしの握り方ではない。釣りから始める。米の炊き方ではない。米を作るところから。

口にする食べ物が「もともとどこにあったのか」「どこでどう作られたのか」を知っているかどうかで、扱い方も意識も変わる。

ウニが高いと思うなら、潜って獲ってみればいい。体験すれば、価値基準は変わる。

そして岡田さんは言う。

自分の価値基準は「自分で獲れるか」「自分で作れるか」にある、と。

「自分で作ればその価値はわかるから。」

すし職人としてのキャリアも、今の複数プロジェクトも、ここに一本で繋がっている。

“現場に触れること”。体験から価値を立ち上げること。

それを人に手渡すことが、岡田大介という人の仕事なのだと思わされた。

💎 映画にするなら──「八方美人最強説」

インタビューの最後、人生を映画にしたら?という質問に、岡田さんは迷いながらも一つに決めた。

「みんなと仲良くする。敵を作らない生き方」。それを自分は“八方美人”と呼びたい。だからタイトルも、これでいい。

海と食を軸に、複数の現場をつなぎ、人を観察し、記録し、喜ばせる。

その姿は確かに、一本の映画のように一貫していた。

🇺🇸英語

Toward a Sushi Chef Who Doesn’t Make Sushi

— Daisuke Okada, President & CEO, Sumeshiya Co., Ltd.

💎 All the work that spread “beyond the counter” began with conversations with customers

Daisuke Okada’s current work is difficult to define in a single phrase.

He is involved with a seaweed company, fishmongers, a tuna fishing company that owns its own vessels, and he is also active as a writer. His engagements span multiple fields.

Yet the beginning was surprisingly simple.

While customers sat at the counter enjoying sushi, company presidents would ask questions:

“Why can you source this fish?”

“How do you prepare it?”

Okada describes himself as “the type who explains everything.” So he answered honestly and thoroughly. The questions kept coming—next time, and the time after that. Eventually, those conversations turned into invitations:

“Would you consider joining our company and putting your knowledge, network, and experience to work inside our organization?”

“They would ask me to come into the company and make use of my knowledge, network, and experience from within.”

The work he does without making sushi was not a carefully planned career shift.

It emerged naturally, as an extension of being needed.

💎 What fishmongers and tuna fishermen needed was not technique, but routes and sales design

What Okada provides to fishmongers and producers is not the craft of sushi itself.

Rather, it is the ability he cultivated as a sushi chef: gathering rare sourcing routes and envisioning how products should be sold in the future.

Fishmongers can still sell fish using traditional methods.

But as people move away from eating fish, there is no guarantee that the future will look the same. Tuna faces the same challenge. It remains popular, yet many companies have aging teams and are not comfortable with SNS or online sales. Something more is needed.

Okada never reduces that “something” to a simple answer like “use social media.”

Selling is not about tools. It is about designing future strategies—considering the reality of the ocean, the future of food, and the stamina of the company itself.

“It’s selling well now, but when you think about the future…”

What is demanded of sushi professionals today is not just skill with a knife.

There is a growing need for people who can see the entire flow—from the sea to the dining table. That sense quietly permeates Okada’s words.

💎 The moment the potential of seaweed ignited: “1,500 kinds—and all edible”

Okada’s encounter with the seaweed company Seavegetable also began with a visit from a friend.

Celebrating a longtime friend who had entered the food world, Okada tasted the seaweed and immediately reacted: “I’ll start using this in my restaurant right away.”

As the conversation deepened, a problem became clear.

Seaweed food culture had stalled. Kombu is for dashi, hijiki is simmered sweetly—and that is where it ends.

Yet Japan has 1,500 varieties of seaweed, all edible and non-toxic. Hearing this, Okada felt his perspective suddenly expand.

“If more varieties are going to appear, we need to show people how to eat them.”

Seaweeds like tosaka-nori are difficult: few people want to buy them, and even fewer know how to cook them. To change that world, menu development was essential.

Okada proposed taking on that role himself—and joined the company.

“There are 1,500 kinds of seaweed in Japan, and all of them can be eaten.”

From sushi as a single point, his focus expanded into the vast world of seaweed.

Okada is consistently drawn to places where the potential of food from the sea lies dormant.

💎 The origin at age 18: When “there was no dinner at home”

Tracing Okada’s roots as a sushi chef leads to a deeply personal experience.

At 18, his mother passed away suddenly at the age of 43. He had much younger siblings, and the family’s eating habits collapsed overnight.

Convenience-store bento boxes. Prepared foods. Choosing only what they liked.

Eventually, physical problems appeared. His younger brother began vomiting at night.

Neither his father nor Okada knew how to cook. Someone had to step in.

Okada made a decision: he gave up university and entered the culinary world.

“I want to become someone who can cook meals for my family.”

Among glamorous paths like Italian or French cuisine, he chose Japanese food—the food eaten daily. From there, he moved into sushi.

“I wanted to become someone who could feed my family.”

His path into sushi was not driven by admiration or prestige.

From the beginning, it was fueled by a sense of responsibility to rebuild life through food.

💎 “The answers are always on site” — A discomfort with vague origins

In the world of culinary training, knowledge alone is never enough. Skill must be built through repetition. Okada practiced relentlessly, even challenging senior chefs directly to sharpen his craft.

After opening his own restaurant, another discomfort emerged at the market.

Boxes labeled Kanagawa, Kagoshima, Kochi—yet vendors would casually say, “This one’s from Chiba.”

Fish circulated without clear origins. Okada could not, in good conscience, serve sushi without knowing where and by whom the fish had been caught.

So he went to the source.

He visited farmers to learn how scallions were grown, who cultivated the daikon radish, and where each ingredient came from.

“All ingredients come from the field. The answers are always there.”

His “obsession” was not a hobby—it was a design for trust.

Every aspect of Okada’s work is rooted in this philosophy.

💎 What a referral-only restaurant cultivated: remembering people

Okada chose a referral-only model for his restaurant.

It sounds elegant—but it is difficult. Proper hospitality requires information.

Remembering names and faces is a given. He notes what guests ate, their preferences, small observations.

For Okada, “personal information” is not about control or intrusion. It is not data for manipulation—it is a key to making people feel safe.

Knowing who introduced them, their background, and what they find comfortable allows him to avoid missteps. This is not an invasion of privacy, but an act of respect with higher resolution.

By linking such details with locations—creating mental “folders” like a Yokohama folder, then district-level folders—people become connected in his mind.

This sharpens conversation, delights guests, and proves effective in both business and private life.

“You can make people happy without spending money—by managing this kind of personal information.”

And the source of that learning was his customers.

At the counter sat business leaders and professionals from many fields. Without realizing it, Okada was being taught.

A sushi restaurant as a place where people raise people—this density shaped his style.

💎 Being “ordinary” made him student council president

Okada describes his school grades as “all threes” on a five-point scale.

Neither exceptional nor poor. Communication was ordinary. It was even a complex.

Yet in middle school, a teacher nominated him as student council president precisely because he was “ordinary.”

He could talk with delinquent students and with those who were bullied or disabled. He could stand in the middle.

As an adult, Okada came to embrace the term happō bijin—someone who gets along with everyone.

Not creating enemies. Even if not everyone becomes an ally, avoiding hostility.

“I believe in the ‘strongest happō bijin theory.’”

This value connects directly to the trust he now earns across multiple organizations.

💎 From “expanding outward” to “carefully re-teaching inward”

When he first became independent, Okada wanted to share the beauty of sushi with the world.

He also wanted to soften the tension of sushi counters—why should those paying feel nervous? Sushi should be enjoyed freely, like Italian food.

But his perspective has shifted.

Sushi has already spread globally. It no longer needs him to “export” it.

What he realized instead was this: sushi had not truly been conveyed to Japanese people themselves.

Now, his focus is inward—reintroducing the true meaning of sushi to both children and adults.

This cannot be done through sushi alone.

Without seaweed, many marine creatures cannot reproduce. To teach sushi properly requires understanding the ocean as a whole.

“It feels like the time has come to carefully rebuild things from the inside.”

Not expanding, but deepening.

Teaching sushi not only as food, but as part of the sea.

This marks Okada’s next phase.

💎 If given one day with middle school students: “Start with fishing”

The educational philosophy he shared at the end reveals his essence most clearly.

If he had just one day with students, he would not teach them how to make sushi. He would start with fishing. Not how to cook rice—but how to grow it.

Knowing where food comes from changes how it is treated.

If you think sea urchin is expensive, try harvesting it yourself. Experience reshapes values.

Okada’s own value system rests on whether something can be caught or made by oneself.

“If you make it yourself, you understand its value.”

His career as a sushi chef and his current projects converge at this single point:

Touching the field. Creating value through experience. Handing that value to others.

💎 If his life were a film: The Strongest Happō Bijin Theory

Asked what he would title a movie about his life, Okada paused—and chose one phrase.

A way of living without enemies, getting along with everyone. That, to him, is happō bijin.

Anchored in the sea and food, connecting multiple sites, observing people, remembering them, and making them happy.

His life, indeed, unfolds like a single, coherent film.

【PROFILE】

岡田 大介(おかだ だいすけ)

株式会社 酢飯屋 代表取締役。すし職人として20数年の経験を持ち、紹介制のすし店運営を通じて食材の現場主義と徹底した“こだわり”を磨く。現在はすしを握るだけに留まらず、海藻・魚・教育・執筆など、海と食に関わる複数プロジェクトに参画。食と海の価値を「現場から伝え直す」活動を深めている。

Daisuke Okada

President & CEO, Sumeshiya Co., Ltd.

With over 20 years as a sushi chef, Okada built a referral-only restaurant that emphasized on-site sourcing and uncompromising standards. Today, he works beyond the counter, engaging in projects involving seaweed, fish, education, and writing. His mission is to reframe the value of food and the ocean by returning to the field—where it all begins.

【PROFILE】

真綺(Maki)

語りの芸術家/インタビュアー/コミュニケーション・スペシャリスト

8年間“しつもん力”を教え、日本語と英語の間で人の想いを橋渡ししてきた。

これまで国内外で、経営者、アーティスト、国際的イベントの登壇者など延べ数千人と対話。

世界的な授賞式や王室叙任式のスピーチ・通訳も担当し、言葉と存在感の両面から人の魅力を引き出す。

Maki

Word Painter / Interviewer / Communication Specialist

For eight years, Maki has taught the art of asking powerful questions, bridging stories between Japanese and English.

She has engaged in thousands of conversations with business leaders, artists, and speakers at international events, both in Japan and abroad.

Her work includes speeches and interpretation for global award ceremonies and royal investitures, capturing and conveying the essence of a person through both words and presence.

経営者の存在感を、言葉とストーリーに刻む。

真綺による日英インタビューにご興味のある企業様はこちらからお問い合わせください。

コメント