🇯🇵日本語

💎 ぷらぷらしていた次男坊が、群馬・渋川で牛飼いになった日

石坂豊さんの仕事は、黒毛和牛の飼育管理、そして出荷までを担う畜産業。拠点は群馬県渋川市だ。

意外なのは、その入口が「家業」でも「農家の血筋」でもないこと。山形生まれの非農家。きっかけは、牛飼いをしていた友人の縁で、群馬の牧場の話が舞い込んだ。そこは三姉妹の家で、跡取りは娘。牧場としては、婿に入って一緒に担ってくれる人を探していた時期だった。一方で自分自身も、定まらないまま“ぷらぷらしていた”時期。結婚をし、石坂さんは牛の世界へ足を踏み入れる。

本人はさらりと言うけれど、人生の偶然が、仕事の必然に変わる瞬間がある。石坂さんのそれは、「次男坊が探されていた」という現実の話から始まっていた。

💎 「農家」に憧れた少年時代と、牛が教えた“効率が正解じゃない”世界

農家に惹かれた原風景は、山形のさくらんぼの季節だった。7月頃になると、友達が一斉に家の手伝いでいなくなる。寂しさと同時に、どこか眩しさが生まれた。

その気持ちが残り、高校卒業後すぐに農家で働いた経験もある。けれど、その後は印刷系の家庭で育った影響もあり、「作る」ことが好きで、家具屋・大工・工場など、いろいろな仕事を渡り歩いた。

そして牛の世界に入ったとき、石坂さんは気づく。

果樹や作物と同じ「農」でも、生き物はまったく別の重みを持つ。作業効率で割り切る発想が、必ずしも正解にならない。思い通りに“つくれない”からこそ、向き合い方が問われ続ける。

💎 「百姓」は“百のことができて一人前”──過去の経験が全部ハマった瞬間

牛飼いは、牛舎で餌をやるだけでは終わらない。環境を整えること、設備に手を入れること、外注すればお金がかかることを自分たちでやること。

石坂さんは、過去にやってきた「いろんな仕事」で身につけたことが、驚くほど全部つながっていく感覚を語る。水道を引く、設備を作る、工夫して手を動かす。牛を中心に、暮らしと経営の“全部”が集まってくる。

この仕事観を象徴するのが、石坂さんの言葉だ。

「百姓っていう言葉が昔あったとしたら、あれは“百のことができて一人前”っていうふうに思ってるんです。」

牛に向き合う現場は、まさに“百の仕事”の集合体だった。

💎 名前をつける牧場の矛盾と、出荷で泣く理由

石坂さんの牧場では、牛に名前がついている。発案者は奥様の「えみ」さん。

本来、牛は産業動物として番号で管理される世界だ。そこに名前をつけるのは矛盾も含む。けれど、えみさんは「番号だけだと楽しくない」と言う。日々呼び名があり、触れ合いがあり、そこに暮らしがある。

当然、出荷の日は寂しい。泣く。

でも石坂さんは、その涙の正体を掘り下げた。出荷を“終わり”として捉えていたから泣くのだ、と。

出荷は終わりではない。そこから肉になり、誰かの食卓に届く。そこまで実感できたら、「別れ」ではなく「つながり」になる。

この気づきが、次の行動を生んだ。

💎 「別れの先」を見たくて、個人ブランドを立ち上げた

石坂さんは、体感を得るために個人ブランドを作る。商売のためというより、「自分の中で出荷を“途中”に変えるため」。

ブランド名は、えみさんの名前と “meat” を掛けた「Emeat(エミート)」。

一頭でもいい。自分たちが育てた牛が、食べる人に届くところまでを感じたい。そういう動機から始まった。

ただ、現実は厳しい。一頭で約500kg。部位ごとに売り先が変わり、生鮮食品としての扱いも難しい。千人単位で届けないと回らない。試してほしいと言われても、在庫や準備に余裕がなく話が進まない時期も続いた。

「発信はしているのに、壁の前で止まっている」──そんな数年があった。

💎 寿司屋が一頭買い。奇跡は“名前”から始まった

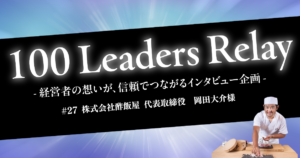

転機は、最初に牧場へ来た料理人との出会いだった。赤ちゃんを連れて見学に来たその人は、「酢飯屋(すめしや)」の岡田さん。

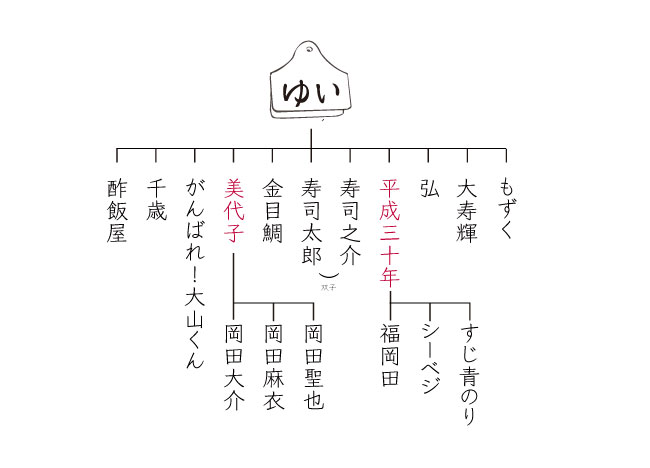

当時生まれたばかりの赤ちゃんの名前が「結(ゆい)」。その記念に、子牛にも「結(ゆい)」と名づけた。ゆいが成長し、母牛になり、そして初めて子どもを産んだとき──遊び心で、その子牛に「酢飯屋」と名前をつけた。

やがて、その「酢飯屋」が出荷の時期を迎える。石坂さんは寂しさから、ただ「出荷しました」ではなく、「ゆいが産んだ酢飯屋が出荷になります」と報告をした。

すると岡田さん側が深く悩み始める。

自分の店の名前を持つ牛を、このままスルーしていいのか。命を預かる料理人として嘘にならないか。

そして、まさかの申し出が来る。

「一緒に頑張りませんか」──。

牛肉の知識がない寿司屋と、販売の難しさに直面していた牧場。どちらも“わかっていない”からこそ、真正面から学び合い、形にしていくことになった。

石坂さんは食育学校に通い、販売の道を探り、岡田さんは寿司職人として「魚と向き合う感覚」を牛肉に持ち込んだ。

そこから10年。毎年、ゆいの子どもたちがつながっていく。名前を知った人が、丁寧に扱う。食べる人の会話が広がっていく。

牧場の中の“矛盾”は、いつしか“関係性の強み”に変わっていった。

※料理人・岡田大介さんについては、

本企画の別インタビューで、その仕事観が語られている。

実は、この「信頼で繋ぐインタビュー企画」のバトンを

石坂さんに繋いでくれたのが岡田さんだ。

タイトルは

「すしを握らないすし職人へ」。

命をどう受け取り、どう人に手渡すのか。

その問いは、石坂さんの仕事とも、静かに響き合っている。

▶︎ 岡田大介さんインタビューはこちら

💎 「身近な人に伝える」ための仕組み──体温を知って扱う人を増やす

石坂さんが描く未来は、むやみに広げる拡大ではない。むしろ逆だ。

買う前に、生産者に会いに来る料理人。牛舎の空気や牛の体温を知ったうえで扱う人。そういう関係性を増やしていきたいという。

繊細な動物だからこそ、丁寧に扱われた方が“能力を発揮する”と信じている。

名前や背景を知れば、雑には扱えない。提供する側も、食べる側も、自然と姿勢が変わる。

「食べづらい」にならない伝え方を探りながら、それでも“牛肉以上の価値”が生まれる瞬間を、石坂さんは実感してきた。

そして和牛の話になると、視点は「日本人の仕事」にまで広がる。

牛の生産には多くの人の手が関わり、部位ごとに楽しむ文化には職人の技術と歴史が詰まっている。海外へという話も、“肉だけ”では成立しない。職人や扱い手まで含めて、初めて和牛の価値が伝わる。

だからこそ、いまは身近な関係性から丁寧に編んでいく。

💎 写真ではなく、絵を描いた理由

牛に名前をつけ、背景や物語を大切にしながら届けていく。

その一方で、石坂さんにはずっと引っかかっていたことがあった。

「伝えたい気持ちはある。でも、伝え方を間違えると、かえって食べづらくなる。」

牛の写真を見せれば、「かわいそう」「残酷だ」と感じる人もいる。

けれど、確かにそこに“生きていた”という事実は、消したくない。

その矛盾の中で、石坂さんが選んだのが――絵だった。

出荷が決まるたび、一頭一頭を思い浮かべながら描く。

仕事が終わったあと、夜な夜な絵の具を広げ、時間をかけて向き合う。

写真ではなく、イラストにすることで、「そこにいた」という証だけを、やわらかく残すためだ。

この“伝え方”は、やがて広がっていく。

牛の物語をまとめた冊子を作り、なぜこの牛がこの店に届いたのかを書き添える。

店によっては、Tシャツを作って渡すこともある。

どれも頼まれたわけではない。勝手に作って、勝手に渡す。

「思いついたら、やらないっていう選択肢がないんですよね。」

石坂さんは笑ってそう言う。

相手が喜ぶかどうか、不安になる前に手が動く。

面倒かどうかを考える前に、やってしまう。

それはサービス精神というより、性分に近い。

面白いのは、そこに“売ろう”という匂いがほとんどないことだ。

使われなくてもいい。捨てられなければそれでいい。

ただ、扱う人が少しだけ背景を知ってくれたら。

食べる人の会話が、ほんの少し広がったら。

牛の名前が、店の名前になり、

絵や冊子が、関係性の記憶として残っていく。

石坂さんがやっているのは、

「物語を売ること」ではなく、

物語が“自然に立ち上がる余白”を用意することなのだ。

💎 子どもたちに見せたいのは、「命」より先にある“愛情の現場”

もし小学生が牧場に来たら何を伝えるか。石坂さんの答えは、少し意外なところにあった。

まず見せたいのは、奥さまが牛に関わる姿。撫で回し、鼻歌を歌い、牛が本当に好きだと伝わる日常。その光景そのものが、「愛情をもって育てられた食べもの」という実感になる。

一方で、命だからいただこう、ありがたく…を強調しすぎる食育は難しいとも言う。重たくなると、食べることが苦しくなる。

大事さは伝えたい。でも、それが目的化すると、本質(=美味しく、笑顔で食べる)を阻害してしまう。

この“バランス感覚”こそ、現場のリアルだ。

印象的なのは、息子さんのエピソード。小学生の頃に気に入って名前をつけた牛が出荷の日を迎えた。このあとどうなるのかしっかり説明はしたけど、当日泣き崩れるのかと思いきや、朝早く起きてトラックを見送り、最後に一言、まっすぐ言った。「この牛の肉、うちに来る?」

「食べたいんだなと思って、まっすぐ受け取りましたね。」

子どもは、逃げない。ドライなのではなく、本質を受け取る強さがある。

その強さが、これからの“つなぎ直す仕事”のヒントになるのかもしれない。

💎 もし人生を映画にするなら──タイトルは「百姓 1/100」

最後に、石坂さんがつけた映画タイトルは「百姓 1/100」。

百のことの中で、いま何個目ができたのか。そんな感覚で生きていく。

完璧な完成形ではなく、今日も“百のうちのひとつ”を積み上げる。

牛飼いの現場は、きれいごとだけでは回らない。矛盾も、涙も、販売の壁もある。

それでも、「別れの先」を見たいと思った人が、関係性を編み直し、食卓までつなげていく。

渋川の牧場で起きているのは、ただの畜産ではなく、体温のある流通と、会話の生まれる食の物語だった。

🇺🇸英語

Hyakushō 1/100

— Connecting What Comes After Goodbye, from a Black Wagyu Farm

(The path of Yutaka Ishizaka, who continues to work with cattle in Shibukawa, Gunma)

💎 The Day a Drifting Second Son Became a Cattle Farmer in Shibukawa

Yutaka Ishizaka raises and manages Black Wagyu cattle, seeing them through from birth to shipment.

His farm is located in Shibukawa, Gunma Prefecture.

What may come as a surprise is how he entered this world.

He did not inherit a family farm, nor was he born into an agricultural lineage.

He grew up in Yamagata, in a non-farming household.

The turning point came through a friend who worked as a cattle farmer.

That friend introduced him to a farm in Gunma run by three sisters.

The successor was already decided—the daughter—but the family was looking for someone who would marry into the farm and take on the work together.

At the same time, Ishizaka himself was in a period of uncertainty, drifting without a clear direction.

Marriage became the pivot point, and with it, he stepped into the world of cattle farming.

He speaks of it lightly, but there are moments when coincidence quietly turns into inevitability.

For Ishizaka, it began with a very real circumstance: a second son was being sought.

💎 A Childhood Drawn to Farming — and a World Where Efficiency Is Not the Answer

His earliest attraction to farming traces back to cherry season in Yamagata.

Every July, his friends would suddenly disappear to help their families.

There was loneliness—but also a sense of admiration.

That feeling stayed with him.

After high school, he worked briefly on a farm.

Later, influenced by growing up in a printing-related household, he gravitated toward making things—working as a furniture maker, a carpenter, and in factories, moving from one hands-on job to another.

When he finally entered the world of cattle, something became clear.

Even though both are called “agriculture,” working with living animals carries a weight entirely different from crops or fruit.

Efficiency does not always lead to the right answer.

Because animals cannot be controlled or “made” exactly as planned, one’s attitude and way of facing them is constantly questioned.

💎 “Hyakushō” — Being Able to Do a Hundred Things

Cattle farming does not end with feeding cows in a barn.

It involves maintaining the environment, repairing equipment, and doing work yourself that would otherwise require costly outsourcing.

Ishizaka says that all the skills he picked up from his many past jobs suddenly connected.

Running water lines, building equipment, solving problems with his own hands—everything converges around the cattle.

Life and management gather in one place.

This outlook is captured in his own words:

“If the word hyakushō existed in the past, I think it meant that you were considered a full-fledged farmer only after you could do a hundred different things.”

The cattle farm is, quite literally, a collection of a hundred kinds of work.

💎 The Contradiction of Naming Cattle — and Why He Cries on Shipping Day

On Ishizaka’s farm, the cattle have names.

The idea came from his wife, Emi.

In the livestock industry, animals are typically managed by numbers.

Giving them names carries an inherent contradiction.

But Emi simply said, “Numbers alone aren’t any fun.”

There are names spoken every day, hands that touch them, and life shared alongside them.

Naturally, shipping day is painful.

He cries.

But Ishizaka began to question why.

He realized he was crying because he saw shipment as an ending.

But it isn’t.

From there, the cattle become meat and reach someone’s table.

If he could truly feel that continuation, shipping would no longer be a farewell—it would be a connection.

That realization led him to his next step.

💎 Creating a Personal Brand to See What Comes After Goodbye

Ishizaka launched a personal brand—not primarily for business, but to reframe shipment as a “midpoint” within himself.

The brand is called Emeat, a blend of his wife Emi’s name and “meat.”

Even one animal would be enough.

He wanted to feel, firsthand, his cattle reaching the people who eat them.

The reality, however, was harsh.

One cow yields roughly 500 kilograms of meat.

Different cuts require different buyers, and handling fresh meat is complex.

To make it work, it needs to reach hundreds—if not thousands—of people.

There were years when people said, “I’d love to try it,” but logistics and timing never aligned.

He kept sharing, but felt stuck in front of an invisible wall.

💎 When a Sushi Chef Bought an Entire Cow — A Miracle Born from a Name

The turning point came through a chef who first visited the farm carrying a baby.

He was Daisuke Okada of Sumeshi-ya.

The baby’s name was Yui, meaning “connection.”

To commemorate that, Ishizaka named a calf Yui as well.

Yui grew, became a mother, and gave birth for the first time.

Playfully, Ishizaka named that calf Sumeshi-ya.

When the time came to ship “Sumeshi-ya,” Ishizaka couldn’t bring himself to say simply, “The cow has been shipped.”

Instead, he wrote, “Yui’s calf, Sumeshi-ya, will be shipped.”

That message stopped Okada in his tracks.

Was it acceptable to let a cow bearing his restaurant’s name pass by?

As a chef entrusted with life, could he ignore it?

Then came the unexpected response:

“Let’s do this together.”

A sushi chef with no knowledge of beef, and a farmer struggling with distribution.

Because neither side fully understood, they learned head-on, together.

Ishizaka studied food education and sales.

Okada brought the same sensibility he used with fish into working with beef.

Ten years have passed since then.

Each year, Yui’s lineage continues.

When people know the name, they handle the meat with care.

Conversations form around the table.

What once seemed like a contradiction on the farm gradually became a strength rooted in relationships.

Related Interview

Chef Daisuke Okada is also featured in another interview within this project.

The title is “Becoming a Sushi Chef Who Doesn’t Make Sushi.”

How do you receive a life, and how do you pass it on to others?

That question quietly resonates with Ishizaka’s work as well.

▶︎ Daisuke Okada Interview

“Becoming a Sushi Chef Who Doesn’t Make Sushi”

https://vividsunshine.co.jp/interview27/

💎 A System for Reaching Those Close to You — Increasing People Who Know the Warmth

The future Ishizaka envisions is not about expansion.

If anything, it is the opposite.

He wants chefs who come to meet the producer before buying.

People who feel the air of the barn and the warmth of the cattle before handling them.

Because cattle are sensitive animals, he believes they perform best when treated with care.

Knowing a name or background changes posture—both for those who serve and those who eat.

While searching for ways to communicate without making meat “hard to eat,” Ishizaka has witnessed moments where value beyond beef itself emerges.

When he speaks of Wagyu, his perspective expands to Japanese craftsmanship as a whole.

Many hands are involved in raising cattle, and the culture of enjoying different cuts reflects deep technical skill and history.

Exporting Wagyu is not just about meat.

Only when the people who handle it are included does its true value come across.

That is why he continues to weave relationships carefully, starting close to home.

💎 Why He Chose to Draw Instead of Photograph

As he values names and stories, Ishizaka wrestled with one concern:

“I want to tell the story—but if I tell it the wrong way, it makes people uncomfortable.”

Photos of cattle can trigger feelings of pity or cruelty.

Yet he did not want to erase the fact that they lived.

So he chose to draw.

Every time a cow is shipped, he paints it—one by one, late at night, after work.

Illustrations leave behind a gentle trace: it was here.

From there, the expression spread.

He created small booklets telling each cow’s story and where it would be served.

Sometimes, he even made T-shirts for restaurants.

No one asked for them.

He simply made them and handed them over.

“Once I think of something, not doing it isn’t really an option.”

There is no strong sense of selling.

It doesn’t matter if they’re used.

As long as someone learns a little background, and conversation opens at the table, that’s enough.

Names become restaurant names.

Drawings and booklets remain as shared memory.

What Ishizaka is doing is not selling stories, but quietly preparing the space where stories can naturally arise.

💎 What He Wants Children to See — Before “Life,” There Is Care

If elementary school students visited the farm, what would he want them to see?

His answer is unexpected.

First, his wife interacting with the cattle—stroking them, humming softly, clearly loving them.

That scene itself conveys what it means to raise food with care.

He is cautious about overemphasizing “life” or gratitude in food education.

When it becomes too heavy, eating itself becomes difficult.

The importance matters—but not when it overshadows joy.

One episode with his son illustrates this balance.

As a child, his son named a cow that was later shipped.

Ishizaka explained what would happen.

On the day of shipment, instead of crying, his son woke early, watched the truck leave, and simply asked:

“Will this cow’s meat come to our house?”

“He wanted to eat it,” Ishizaka says, “and he accepted it directly.”

Children do not avoid the truth.

They possess a strength to receive the essence.

That strength may hold the key to reconnecting what we pass on.

💎 If This Life Were a Film — The Title Would Be Hyakushō 1/100

If Ishizaka were to title his life as a film, it would be Hyakushō 1/100.

Out of a hundred tasks, how many have I learned so far?

There is no perfect completion—only the daily accumulation of one more.

Cattle farming is not idealistic.

There are contradictions, tears, and walls that don’t move.

Still, someone who wants to see what comes after goodbye continues to reweave relationships, connecting them all the way to the table.

What unfolds on a farm in Shibukawa is not merely livestock production.

It is a circulation with warmth—where conversation is born.

【PROFILE】

石坂 豊(いしざかゆたか)

群馬県渋川市にて黒毛和牛の飼育・管理・出荷を行う畜産業者。山形県出身の非農家から牛の世界へ転身し、現場を担う。牛に名前をつける牧場運営を通じて、「出荷の先」までを実感できる関係性づくりを重視。個人ブランド「Emeat(エミート)」を立ち上げ、料理人・店舗との対話と学び合いを重ねながら、和牛の価値を“体温ごと”届ける取り組みを続けている。

Yutaka Ishizaka

A cattle farmer based in Shibukawa, Gunma Prefecture, raising, managing, and shipping Black Wagyu.

Originally from Yamagata and from a non-farming background, he entered the world of cattle through marriage.

By naming each animal, he focuses on building relationships that extend beyond shipment.

He founded the personal brand Emeat, working closely with chefs and restaurants to deliver the value of Wagyu together with its warmth and story.

【PROFILE】

真綺(Maki)

語りの芸術家/インタビュアー/コミュニケーション・スペシャリスト

8年間“しつもん力”を教え、日本語と英語の間で人の想いを橋渡ししてきた。

これまで国内外で、経営者、アーティスト、国際的イベントの登壇者など延べ数千人と対話。

世界的な授賞式や王室叙任式のスピーチ・通訳も担当し、言葉と存在感の両面から人の魅力を引き出す。

Maki

Word Painter / Interviewer / Communication Specialist

For eight years, Maki has taught the art of asking powerful questions, bridging stories between Japanese and English.

She has engaged in thousands of conversations with business leaders, artists, and speakers at international events, both in Japan and abroad.

Her work includes speeches and interpretation for global award ceremonies and royal investitures, capturing and conveying the essence of a person through both words and presence.

経営者の存在感を、言葉とストーリーに刻む。

真綺による日英インタビューにご興味のある企業様はこちらからお問い合わせください。

コメント